The Great Betrayal: The Colonisation of Bharat by India

It is a long, tongue-twister of a name for a government scheme – ‘Viksit Bharat—Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin)’. It is even more torturous to read if you are not a Hindi speaker.

This is the name of the new scheme, which will replace the two decade old Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act or MNREGA. Claimed to be an improvement over its predecessor, it is in fact a calculated dilution of the most critical lifeline for India’s rural poor

The priority for the devious minds behind this terminological assault was not really details of the scheme itself – they were aiming to arrive at the politically convenient acronym ‘G RAM-G’. An abbreviation, which plays on the name of Lord Ram, who has been politically hijacked by the ruling BJP for over three decades, first to achieve power and ever since to desperately hang on to it.

The main target of this convoluted exercise is obviously the masses of the Hindi belt, where Lord Ram is supposed to have millions of devotees, most of them rural and unemployed. For any ruling regime, no welfare scheme has any merit on its own, unless it results in political capital they require for re-election.

The change of nomenclature, though, is only part of a more diabolical game. The new, revamped scheme is meant to rob the essence of the MNREGA initiative, brought in by the UPA government in 2006 to address rural joblessness.

“What was essentially a “right to a job” scheme has been reduced to a discretionary welfare scheme’ Saptagiri Sankar Ulaka, a Congress MP from Odisha, who heads the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Rural Development and Panchayati Raj told the Indian Express.

For years, MNREGA served not just as a welfare check but as a floor for rural wages. It disrupted the absolute control that rural landlords historically held over landless labourers by providing an alternative source of income. Furthermore, it has been a driver of gender inclusion, with women consistently accounting for over 50% of the person-days generated, providing financial autonomy in deeply patriarchal regions. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the scheme proved its worth as the only fallback for millions of migrant laborers returning to their villages.

By restricting work opportunities and reducing real-term funding, the new scheme appears to reverse this progress, effectively tilting the scale back toward a feudal balance where landed elites regain dominance at the cost of the vulnerable.

While earlier MNREGA was funded entirely by the Union government now states will have to bear 40% of the costs. According to opposition leaders, this will place a huge financial burden on the states, and many will struggle to implement it. There are also worries that the union government will discriminate in the allocation of funds to states ruled by non-BJP parties – making G RAM-G one more weapon to attack India’s already fraying federal system with.

The “Band-Aid” Reality

A step back first to point out here that MNREGA, despite its positive aspects, functioned primarily as a band-aid for the deep-seated structural gangrene of rural poverty. While it successfully prevented starvation and destitution for millions, it failed to integrate with broader reforms in land rights, infrastructure, and skill development. In other words, it ‘managed’ rural poverty rather than eradicating it.

There were problems with implementation too. While the Act promises 100 days of work, government data reveals that the national average often hovers between 45 to 50 days per household (1). Furthermore, recent analyses highlight chronic issues with delayed payments and rejected transactions due to complex digital attendance systems, which discourage the very poorest from participating.

What the Modi government’s move to dismantle even this patchy safety net confirms though, is a stark, uncomfortable truth: the rural poor have never been a priority for the country’s ruling elites. The latest legislative betrayal is just one more symptom of India’s greatest festering wound— one broader and bigger than any other class or caste divide in the country — which is the power and wealth divide between rural and urban India.

A Majority Betrayed

India prides itself on being the world’s largest democracy, a system where numbers are theoretically supreme. By this logic, rural India should be the undisputed kingmaker of national policy. According to the latest population projections, nearly 64-65% of Indian citizens continue to reside in rural areas. (2)

These villages are the primary residence of the nation’s most marginalized communities—the Dalits, Adivasis, and Backward Classes—who constitute the vast majority of the rural demographic and also India in its entirety.

Yet, the current political reality presents a grotesque inversion of democratic logic. Political parties across the spectrum have increasingly transformed into mouthpieces for and agents of corporate and urban elites. While political leaders dutifully visit villages to solicit votes during election cycles, the policies they enact are drafted in the glass-and-steel boardrooms of the metropolises, far removed from the agrarian reality.

The evidence of this systemic neglect is embedded in the annual Union Budget itself. The current Indian government has aggressively pursued a policy of corporate benevolence. In September 2019, it significantly reduced the corporate tax rate for existing domestic companies from 30% to 22%, provided they did not claim any exemptions or incentives. An even lower rate of 15% was introduced for new manufacturing companies incorporated after October 1, 2019. The initial estimated annual revenue loss was around ₹1.45 lakh crore. (3)

In subsequent years, the annual tax income foregone hovers around the ₹1 lakh crore mark. All this was done in the name of stimulating economic growth, attracting new investment, and boosting employment – to be precise, urban employment.

Simultaneously, the persistent demand for a legal guarantee of Minimum Support Price for farmers is frequently dismissed by policymakers as “fiscally irresponsible.” The paradox is glaring: the state finds the fiscal space to write off over ₹4 lakh crore in corporate loans (4), yet pleads poverty when asked to ensure that the farmers who feed the nation can afford to feed their own families. The rural citizen, it seems, is a valued voter on election day but a second-class subject every other day.

Internal Colonization: The Structure of Inequality

To understand the persistence of rural poverty, one must stop viewing it as an accidental by-product of development and recognize it as a feature of design. The systematic neglect of rural populations in terms of income, health, education, and infrastructure constitutes a form of “internal colonization.” Much like the colonial economic models of the 19th and 20th centuries, which extracted wealth from the Indian subcontinent to fund industrial growth in Europe, today’s urban-centric economic model extracts value from rural India to fuel the expansion of metropolitan cities.

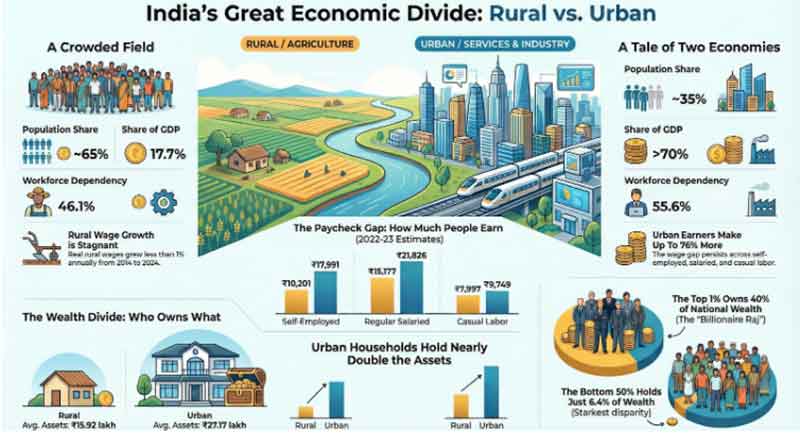

The economic data paints a damning picture of this extraction. Agriculture currently employs a staggering 46.1% of India’s workforce, yet it receives only about 17.7% of the national income (5) (6). This fundamental imbalance means that nearly half of the country’s population is competing for less than one-fifth of the economic pie. The result is a humiliating disparity in income and living standards. Rural earnings from self-employment are significantly lower than in urban areas, with a gap of around 40 per cent between the two (7).

While the national discourse in urban centres revolves around “start-ups,” “AI,” and “trillion-dollar economies,” real wages in rural India have flatlined, growing at less than 1% annually for the last decade (8). This stagnation is not a lag in development; it is the mathematical result of an extractive economic architecture.

The Theft of Opportunity: Health and Education

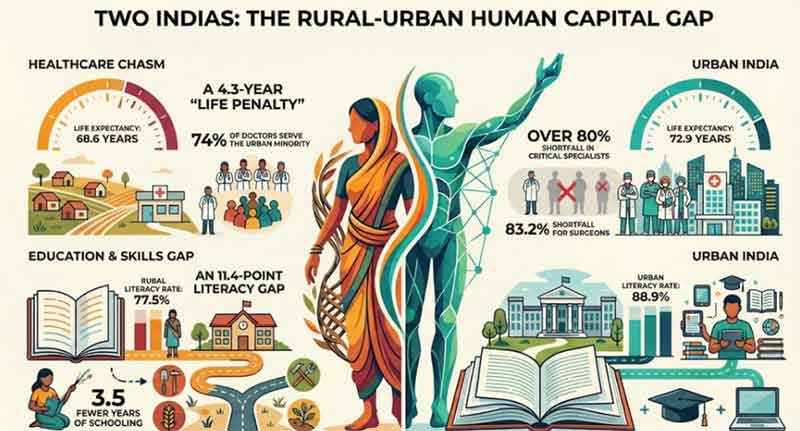

The impact of this internal colonization is most brutal in its denial of basic human capabilities—specifically in health and education. The accident of birth now determines the length of one’s life. A child born in an Indian village is statistically destined to live a shorter life than one born in a city. Life expectancy in rural India stands at 68.6 years, compared to 72.9 years in urban areas (9). This gap of over four years represents life stolen simply due to geography.

The reason for this disparity is a crumbling infrastructure of care. Urban areas, home to only 35% of the population, hoard 74% of the country’s doctors (10) (11). In rural Community Health Centres (CHCs), which are mandated to provide specialized care, there is an 83% shortage of surgeons and a 74% shortage of gynaecologists (12). For a rural woman facing childbirth complications or a farmer suffering a serious injury, the breakdown of the public health system sends a chilling message: you are on your own.

A similar story of neglect unfolds in the education sector, where rural youth are being systematically de-skilled. The “Mean Years of Schooling” in rural areas is just 6.4 years, compared to 9.9 years in cities (13). This 3.5-year gap functions as a wall, preventing rural youth from accessing the modern economy. Without the requisite skills to participate in high-value sectors, they are trapped in low-paying labour, ensuring that the cycle of poverty remains unbroken for the next generation. This suppression of potential is not merely a policy failure; it is a denial of the rural population’s right to modernize.

The Ecological Front: A Crisis of Survival

Compounding the economic and social distress is an ecological crisis that threatens the very survival of the countryside. Climate change is no longer a distant theoretical threat; it is a present reality hitting rural India with disproportionate force. While urban elites may view rising temperatures as a discomfort to be managed with air conditioning, for the farmer, extreme heat translates directly into destroyed crops and wiped-out livelihoods. Yields of staple crops like wheat and maize are already under threat from rising temperatures.

However, this crisis is also man-made, driven by policies that have historically prioritized short-term yield over long-term sustainability. The “Green Revolution” model, which incentivized water-guzzling crops and the heavy use of chemical fertilizers, has turned vast tracts of soil toxic and pumped aquifers dry. Today, 85% of rural drinking water is sourced from groundwater, which is being mined faster than nature can replenish it. In many regions, the remaining water is chemically compromised; 20% of groundwater samples across India now display unsafe nitrate levels, while others are laced with arsenic and uranium (14). Continuing down this path of chemical-intensive, water-inefficient agriculture is tantamount to ecological suicide.

A Blueprint for Regeneration

What the subversion of the MNREGA scheme by the Modi regime really shows is that changes in the power balance between the city and village in India cannot be brought through any kind of top-down process. The ‘benevolence’ of well-meaning individuals or politicians pushing through progressive legislation is never going to be sustainable.

Resolving the divide between “India” and “Bharat” is not just a policy option; it is a moral and existential necessity. And one that requires a fundamental shift from an economy of corporate extraction to one of rural regeneration.

For this to happen there has to be a wider awakening of rural India, which, in alliance with the urban poor (themselves mostly rural migrants) radically changes the power balance in the country away from the cities to the villages of India. This is what Mahatma Gandhi, whose name adorned the MNREGA initiative for two decades, really wanted – to place the Indian village at the centre of all national policy-making.

While Gandhi sought to convince through persuasion, personal example and peaceful means, it is clear that these methods alone are not going to work. The vested interests behind city and industry-centric development are too powerful and entrenched to respond to mere reason or logic or appeals for compassion.

What India needs today is nothing less than a homegrown version of the French Revolution. If the masses are being told to have cake when there is no bread, they should be ready to take off the ruling, corporate monarchy’s head.